There are no items in your cart

Add More

Add More

| Item Details | Price | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Anshuman

Address Resolution Protocol (ARP) is the quiet matchmaker that lets IPv4 addresses find the right MAC addresses on a LAN, then remembers those pairings for faster conversations later on.

Why ARP exists

When a device sends traffic, the packet carries IPv4 addresses, but the Ethernet frame that actually crosses the wire needs MAC addresses. ARP fills this gap by mapping a destination IPv4 address to its corresponding MAC address so the sender can build a valid frame and get the packet on the network. ARP does two core jobs: resolving addresses on demand and caching those mappings locally so every new conversation does not have to start with a broadcast.

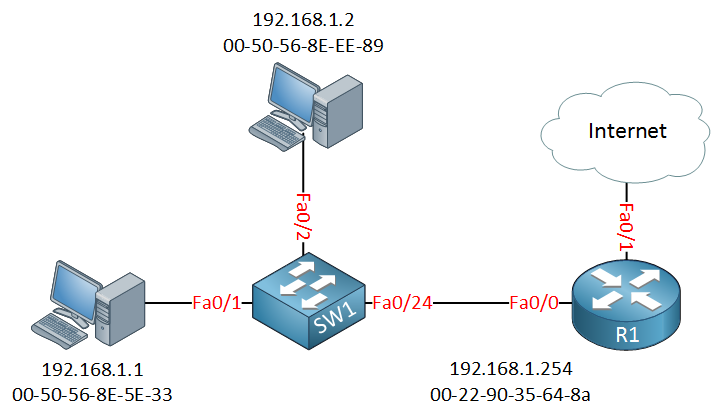

Talking to neighbors

If a host sees that the destination IPv4 address is on the same subnet, it can ask directly for that device’s MAC address using ARP. For example, a host with address 10.10.1.241/24 wanting to talk to 10.10.1.175 first decides that both live on 10.10.1.0/24, then sends a Layer 2 broadcast (FF:FF:FF:FF:FF:FF) asking which device owns 10.10.1.175 and requesting its MAC. The owner replies with an ARP response that includes its MAC address, and both ends can now update their tables and exchange frames normally.

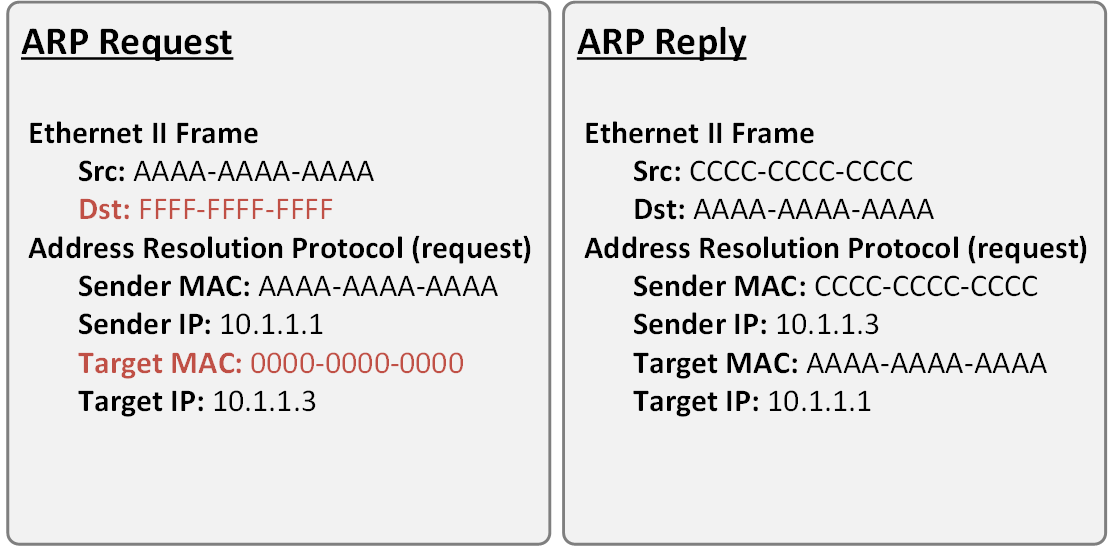

What Wireshark reveals

A packet capture of this exchange shows the ARP request as an Ethernet frame sourced from the host’s MAC, destined to the broadcast address, and carrying an ARP payload that repeats the sender’s MAC and IPv4 alongside the target IPv4. The sender’s MAC appears both in the Ethernet header and inside the ARP payload because the L2 header is discarded during decapsulation, so the receiving ARP process needs the address preserved in the payload to learn and cache it. The reply frame reverses the roles: now the target includes its own MAC with the requested IPv4 so the original sender can complete its binding.

Crossing subnet boundaries

When the destination IPv4 address is on a different subnet, the host cannot ARP directly for the remote device and instead needs the MAC address of its default gateway. A host such as 10.10.1.241 sending to 10.10.2.55 recognizes that 10.10.2.0/24 is remote and therefore wraps the packet in a frame whose destination MAC is the router’s interface (for example, 10.10.1.1 on the local segment). To do that, the host broadcasts an ARP request for 10.10.1.1, receives the router’s MAC in the ARP reply, caches it, and then forwards the traffic toward the gateway.

Life inside the ARP cache

Every IPv4 device maintains an ARP table in memory that stores recent IPv4–MAC bindings for local devices, including the default gateway. Before sending a frame, a host checks this table; if a matching entry already exists, it can skip broadcasting and use the cached MAC, otherwise it triggers a new ARP request and then stores the result. Entries are created and updated dynamically, expire after a timeout (for example, several hours on typical Cisco devices and only a few dozen seconds—chosen randomly—on many Windows systems), and are regenerated automatically the next time communication is needed.

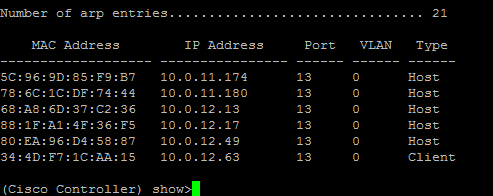

Peeking at ARP tables

On a Windows PC, the arp -a command shows the current ARP cache for all interfaces, and adding -N ip_address limits the view to a single interface. On Cisco IOS routers, show ip arp and show arp list the learned IPv4–MAC mappings per interface, and optional parameters like IPv4 address, hostname, MAC address, or interface let you focus on specific entries. If no ARP reply ever comes back for a request, the device cannot build a proper frame, so the original IPv4 packet is dropped because there is nowhere valid to send it.

Anshuman

Network Engineer JNCIA | PCNSA | Network Security Solutions